Kurt Vandaele, Senior Researcher at the European Trade Union Institute, looks at how young workers can be attracted into trade unions

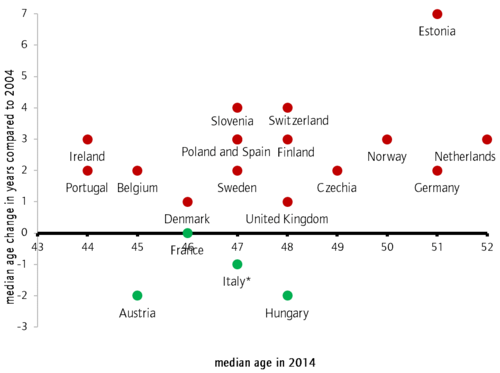

The percentage of employees paying union dues has almost universally declined across Europe in recent decades. Moreover, much of the unions' existing membership base is generally 'greying', with many members aged in their mid-40s to early 50s, as Figure 1 below shows.

Figure 1. Median age of union members in 2014 and its change compared to 2004 in Europe. Source: European Social Survey. The original survey question refers to membership of a union or similar organisation. *Italy: 2012 data.

In terms of organising, young people are considered to be the most 'problematic' of the different categories of under-represented groups in unions.

If the difficulties in organising them are not addressed, other existing or new organisations might emerge to represent them, particularly in specific segments of the labour market like the 'gig economy'.

So what could unions do to reconnect with young workers?

There is no such thing as widespread anti-trade unionism. Virulent anti-trade unionism among young people is definitely not the problem. Certainly, tensions between young activists and unions exist, but these should be put into context. Often they can be linked to inadequate union strategies, as has been the case in several southern European countries since the Great Recession.

Young people's attitudes towards unions are in fact (critically) supportive"Š"”"Ševen in the United States. Time and again, however, many trade unionists tend to believe popular narratives that emphasise generational stereotypes, as an explanation for low youth unionisation rates.

The role of unions is not clear to most young people, a problem that can be explained by the dwindling presence of parents, relatives and friends who support unionisation. Such union-friendly social networks increase the likelihood of a young person developing a favourable attitude towards unions, but these networks are shrinking in sectors or countries where unions are in decline.

This (much) weaker transmission of pro-union attitudes has therefore made unions 'unfamiliar' to youth prior to their entry to the labour market. Unions across Europe have seen this lack of deeper union knowledge as a chance to inform young people about their role and about social rights (see here and here for examples of outreach activities). But once young people make the transition from school to the labour market it is crucial that they also find a union in their workplace, which is often not possible.

Labour market experience for youth must be a priority focus

The hostility of employers to union membership and a fear of victimisation among young people further contributes to a low rate of youth unionisation. Above all, today's school-to-work transitions are plagued by precariousness, and the quality of youth jobs has deteriorated sharply in recent years, with a rise in part-time, insecure and temporary work.

Therefore, union strategies around precarious work are of fundamental importance. Unions should reflect upon how they could develop organising strategies focused on a life-cycle approach instead of only a job-centred one.

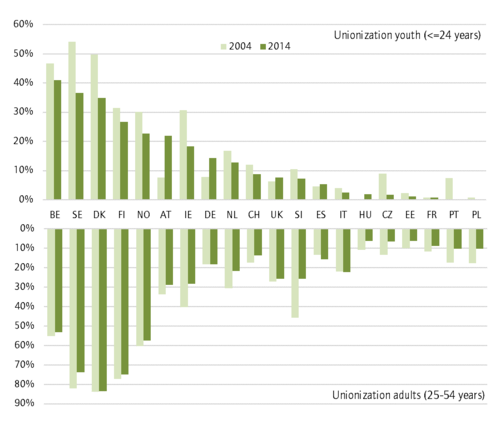

Figure 2: Young people are more likely to be employed in workplaces and economic sectors where union presence is already weak

Unionisation rates among youth and adults in Europe, 2004 and 2014. Source: See Figure 1.

Unions that are institutionally entrenched in labour markets are able to lower the cost of organising or servicing workers. This certainly applies to unions in Belgium and the Nordic countries, whose strong 'embeddedness' in school-to-work transitions allows young people to gauge the benefits of membership first-hand.

Figure 2 demonstrates that these are the countries that recorded high youth unionisation in both 2004 and 2014. The graph also reveals that a high youth unionisation rate leads to a high adult unionisation rate. Early unionisation is therefore the key.

As the window of opportunity becomes smaller the older workers get, unions must demonstrate their relevance in the school-to-work transition of young people. A good start for engaging young people would be to map what proportion of them are exposed to trade unionism and to analyse their experiences at work.

Redesigning internal structures

If necessary, unions should also address their own current statutes and representation structures. Their current set-up might act as an obstacle to union membership for those workers frequently changing employment status. Also, unions' structures and predominant (decision-making) culture may appear unattractive, and can be unfavourable for youth participation in union democracy and action.

Today's age-based union structures for youth, if and where they are in place, are insufficient for instigating a more transformative change in union strategies and practices.

One way of tackling this would be to experiment with participatory democracy and informal engagement around such issues as precariousness. Fostering alliance-building between unions and relevant youth organisations, like student organisations, is another way to gain a better understanding of youth issues, including those outside the workplace. Training and education via mentoring and union leadership development programs could do even more to empower young unionists.

Decisive union action is needed

Unions could help to revive the weakened traditional motives for membership by promoting the principle of solidarity. A good example of this approach is the successful Dutch 'Young & United' campaign that achieved the partial abolishment of the youth minimum wage. Instead of a top-down approach, the campaign gave room to youth-led activism by escalating direct action, giving young people the confidence that their own contribution could make a difference to achieving a better regulation of the labour market.

The campaign engaged them based on like-by-like recruitment, but did not address these young people as an age-defined group. Instead, by focusing on the youth minimum wage, a collective identity was forged based on a salient workplace issue that matters to them today.

Making heavy use of social media, this issue-based campaign seemed effective at tapping into youth networks by using a language, visuals and messages that appealed to young people; it presented a different public image of unions.

But many unions still have a lot to learn about communication policies for engaging young people, whose preference for social media is based on the opportunities it offers for participation.

A vast shift in resource allocation is needed to overcome the widening representation gap and to turn small-scale, local initiatives into large-scale organising efforts, especially in those growing occupations and sectors where young workers are employed and need unions the most.

There is no intergenerational shift that dooms youth unionisation to failure. Therefore, unions should not resign themselves to such a fate, but recognise that there is still room for manoeuvre and, it must be stressed, the sooner the better.

Learn more about Youth Connect, the Congress programme of engagement with secondary schools