The history of Irish trade unions stretches back into the eighteenth century, when local societies were established in the cities to represent craftsman such as bricklayers butchers and printers. In the mid nineteenth century new unions covering Britain and Ireland were established and rapidly put down roots.

1889

From about 1889 a new type of union began to emerge in Ireland. These unions aimed to organise the mass of skilled workers, and separate unions covering dockers railwaymen and general workers were established in these years, with branches springing up in Ireland.

The Irish Trade Union Congress (ITUC) was founded in 1894, three years after the death of Parnell. Its stated aim was to act as the collective voice of organised Irish labour.

New unions began to establish themselves from 1907, with the arrival in Ireland of James Larkin as an organiser for the British dockers' union. Two years later he was dismissed by that union, following a disagreement on policy and established the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union. This union expanded rapidly and in doing so incurred the hostility of the employer class, which culminated in the Dublin Lock Out of 1913.

1912

In 1912, partly under the influence of James Connolly, the ITUC established a political arm and became known as the Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Congress (ILPTUC). At its 1916 congress a motion was passed expressing sympathy with all those who had died for their beliefs.

1918

During the 1918 election, the Labour Party famously stood aside to give the national independence movement a clear run and turn the election into a virtual referendum on independence. For the majority of working people this was their first time voting.

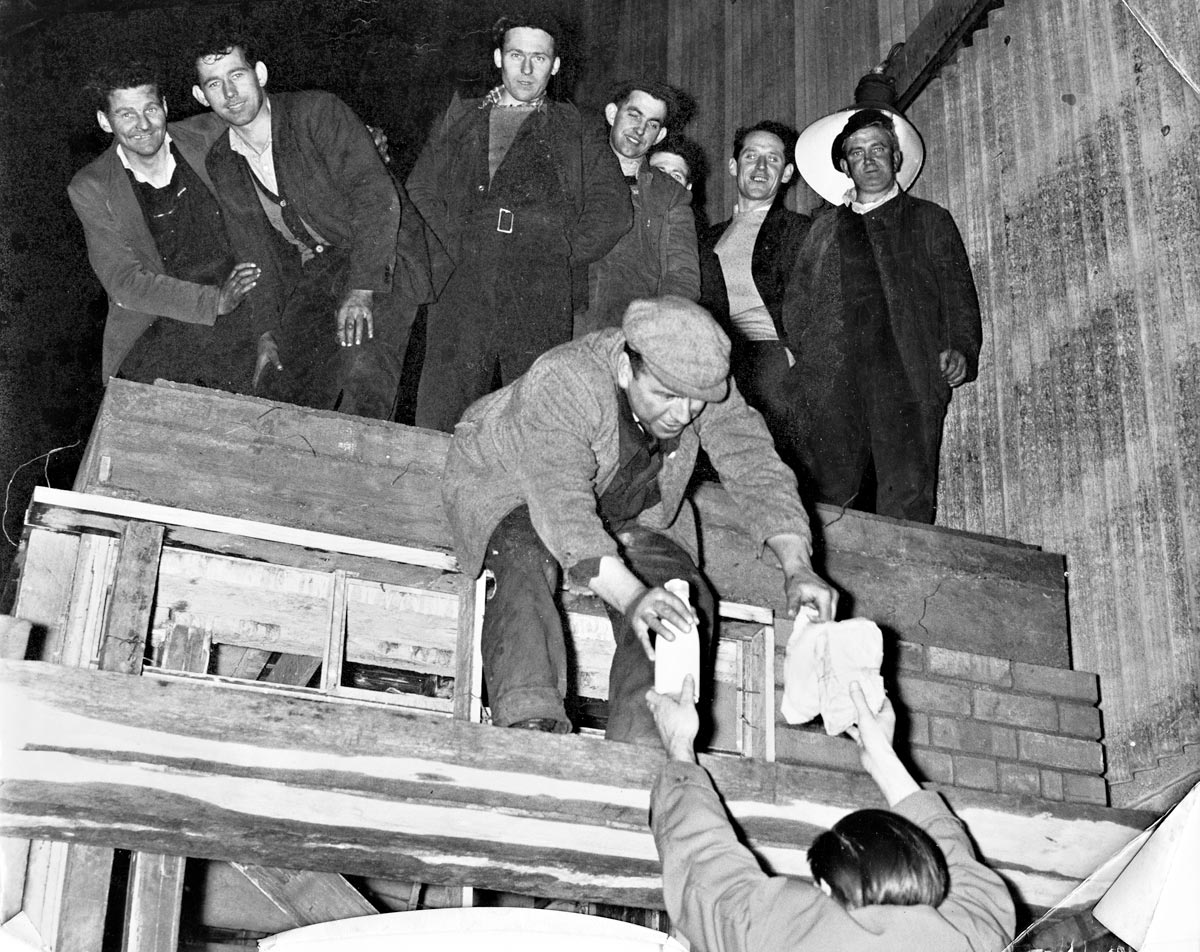

During the War of Independence, Congress coordinated one day strikes in favour of the release of political prisoners and sympathetic action by railwaymen, who refused to assist in the transport of British troops.

In the run up to civil war, ILPTUC officers attempted to broker a deal, urging anti-treatyites to accept the will of the people as demonstrated in the June 1922 election, while voicing sustained opposition to the inflexibility of the government and the ill treatment of prisoners.

1920s

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 established Northern Ireland, thus giving organised Irish labour the unique distinction of organising in two political jurisdictions. This was made even more complex by the fact that many of the affiliated unions had their head offices in the UK.

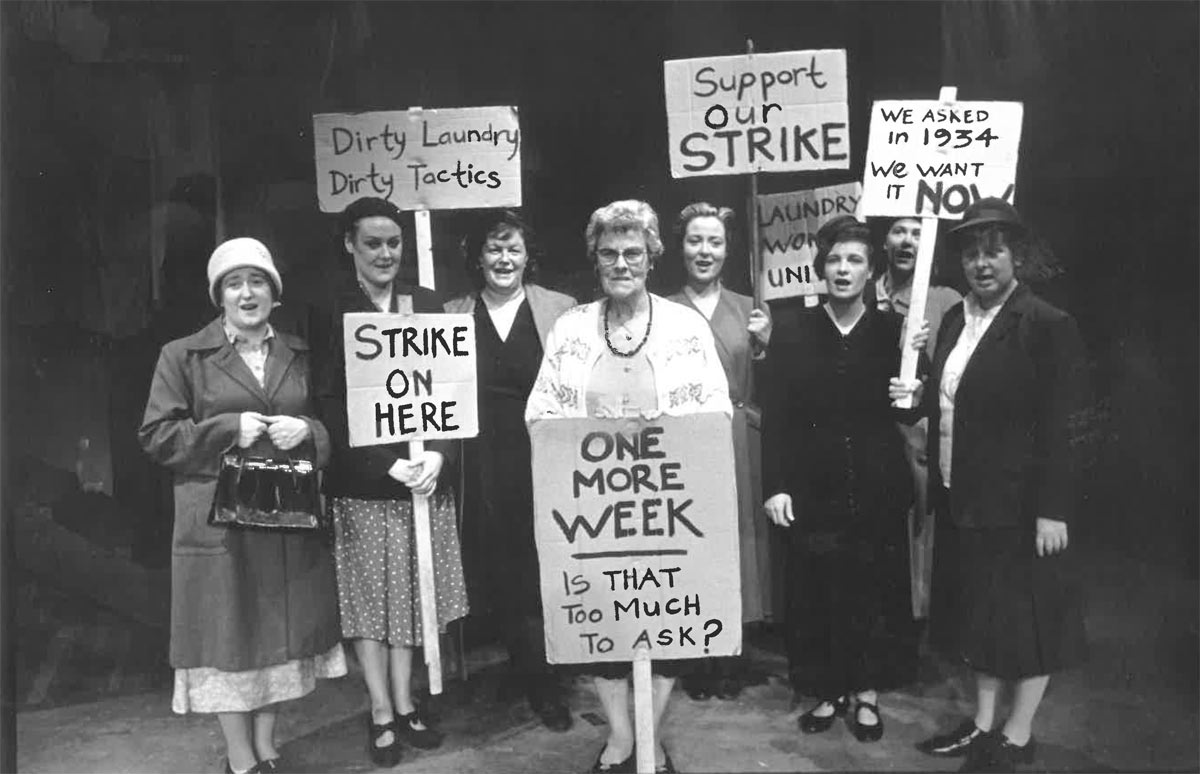

The 1920s and 1930s saw the country mired in economic depression and falling living standards. In 1930 the Labour Party and the Congress separated amicably.

1940s

During the 1940s tensions developed around the role of the charismatic but mercurial Jim Larkin and in relation to Irish and British-based unions. This culminated in a 1945 split, with the Irish-based unions forming the Congress of Irish Unions. One small bright spot on the horizon was the formation of the Northern Ireland Committee (NIC) of the ITUC, in the same year.

1950s

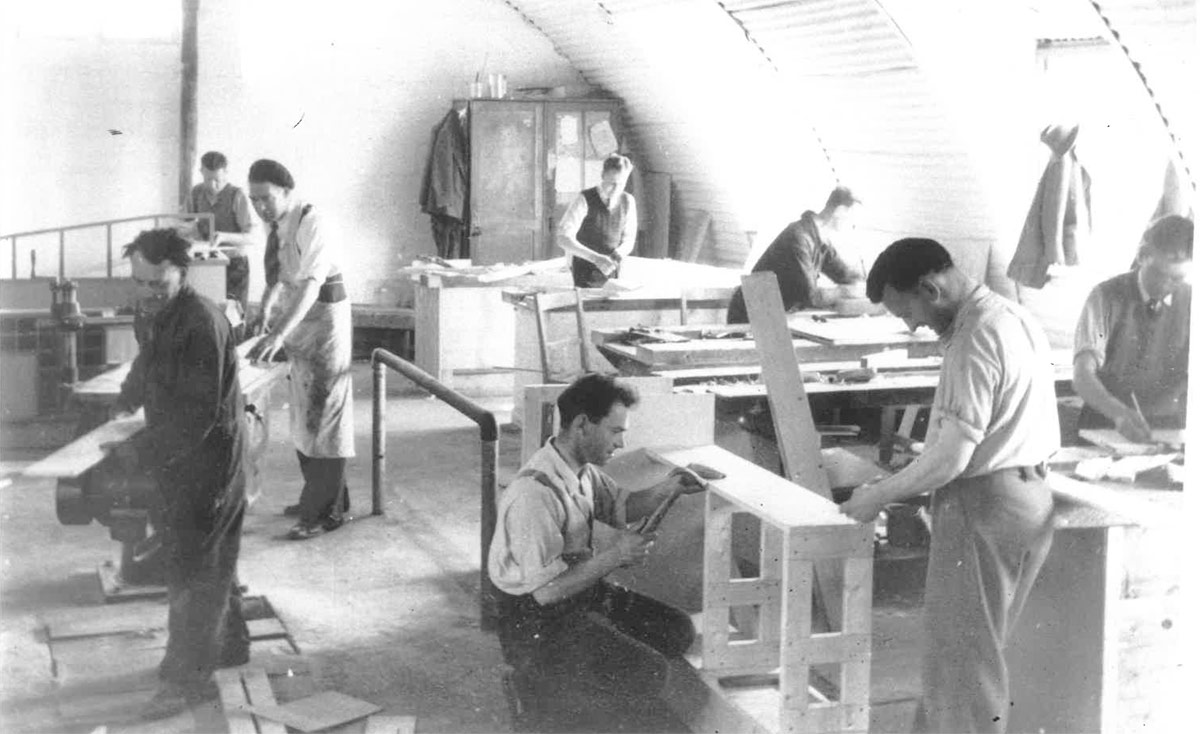

The 1950s were a truly dreadful decade in Ireland, with emigration and poverty at record levels. The opening up of the economy with the First Programme for Economic Expansion in 1958 and the retirement of de Valera in the same year, quickened the pace of change.

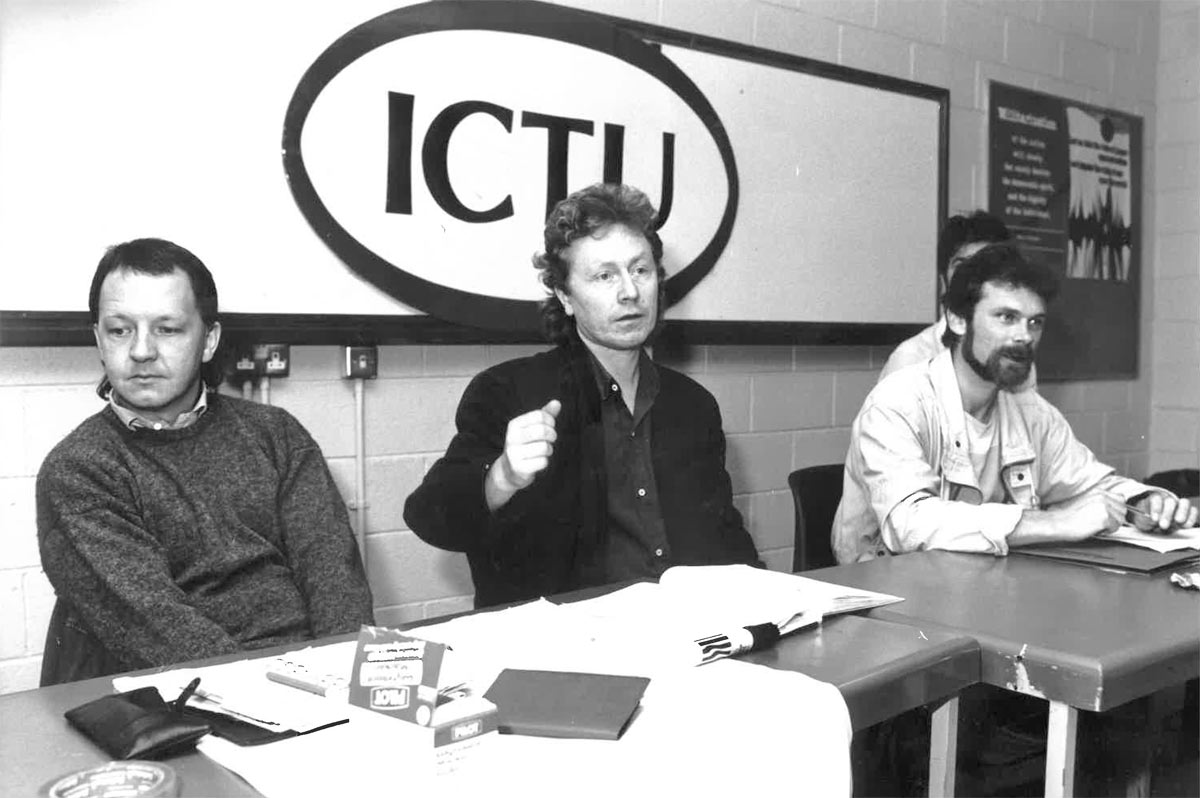

In 1959 following years of behind the scenes discussions the two union federations formally reunited, becoming the Irish Congress of Trade Unions (ICTU). An early win for the new body was in the 1959 referendum on the retention of proportional representation in voting, where the narrow vote for retention was attributed to an effective trade union campaign.

1960s

The newly-united union movement coincided with in the expansion of the economy in the 1960s and the Northern Ireland Committee was formally recognised by the Northern Ireland government in 1964.

When conflict erupted in 1969, the Northern Ireland Committee took a resolute anti-sectarian stand and is credited with preventing the conflict from spilling over into workplaces.

1970s

The high rates of inflation that followed on the oil price shocks of the 1970s meant that wage increases were eroded not only by inflation but by an increasing tax take.

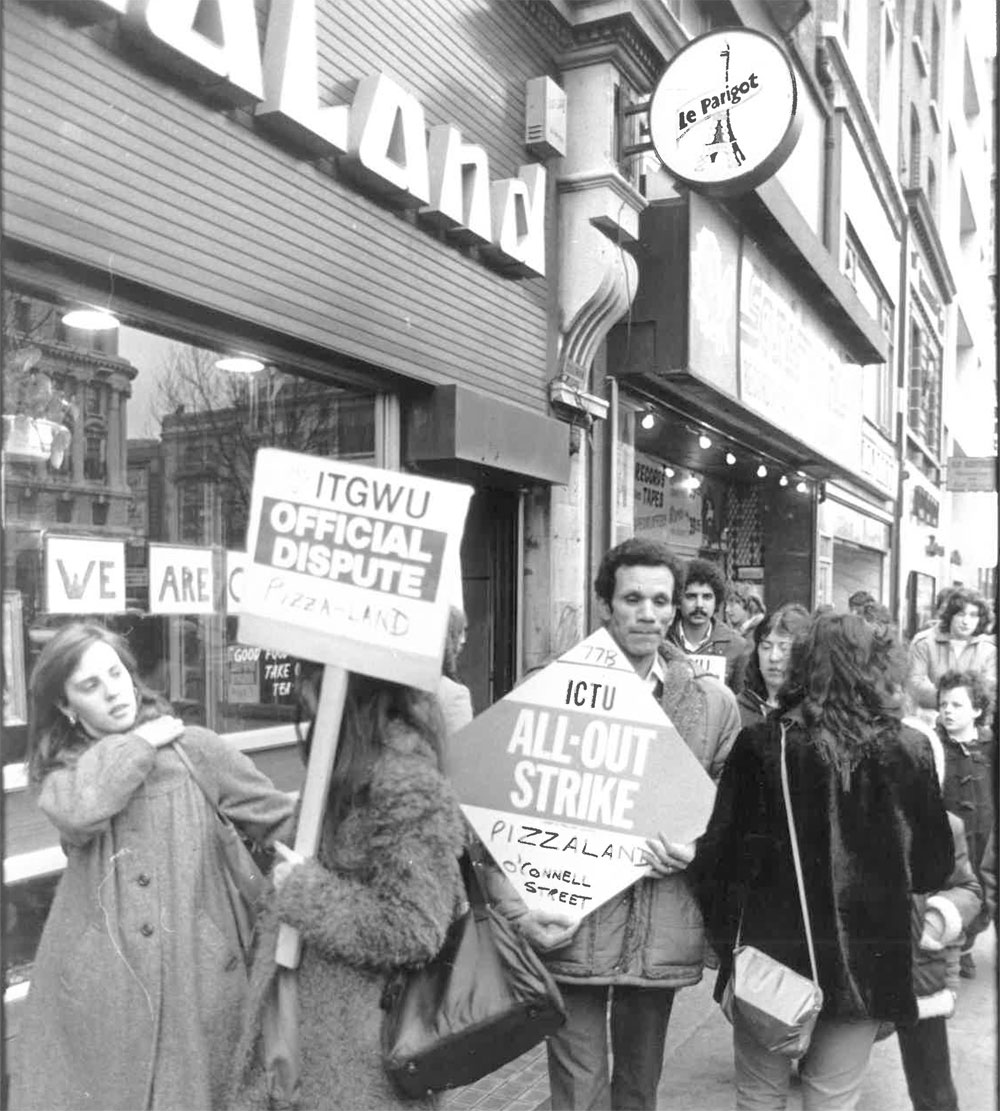

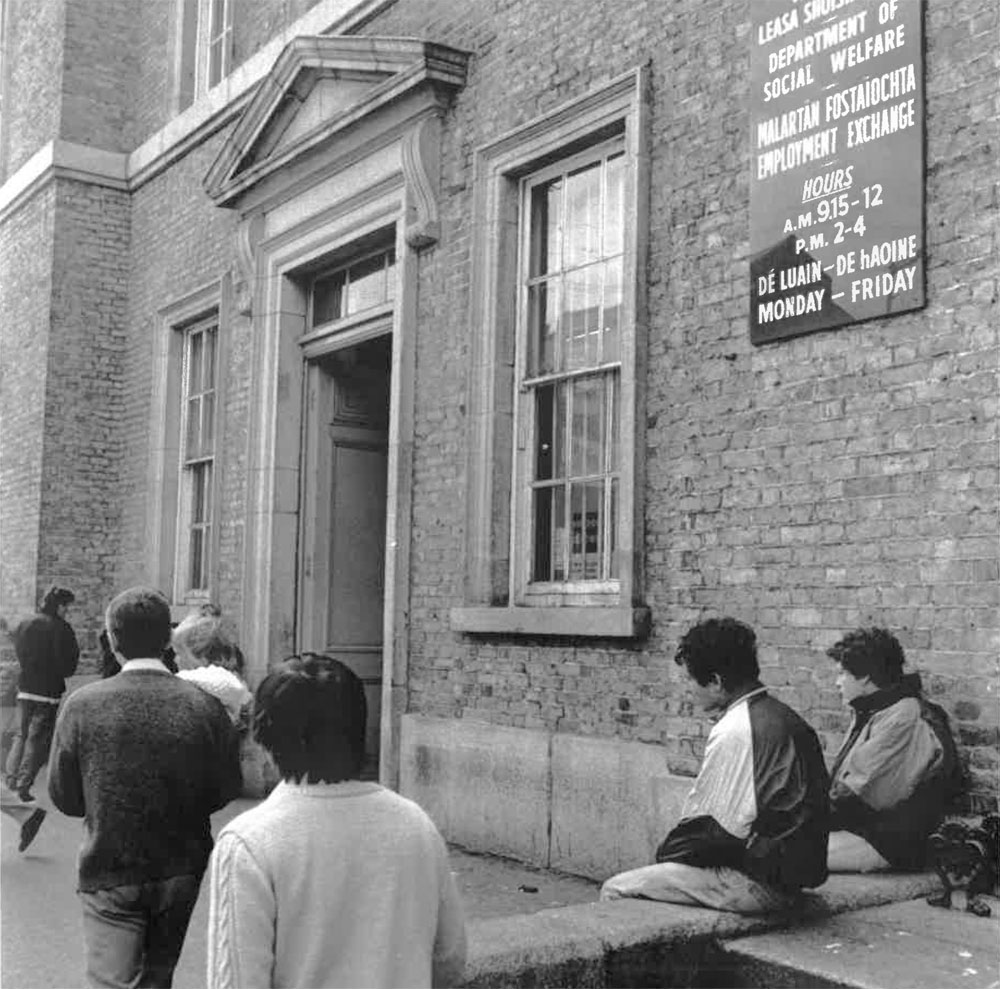

A series of protests initiated by the Dublin Council of Trade Unions brought crowds onto Dublin streets of a size unseen in Europe, until the fall of the Berlin wall later in the decade. However, the 1980s threatened to be a full scale repeat of the 1950s, in terms of emigration and job losses.

1980s

In 1987, an initiative from the ICTU led to the negotiation of the first of the current social partnership agreements, the Programme for National Recovery. And the rest, as they say, is history.

In 1994, as the Celtic Tiger began to take shape Congress celebrated its centenary and in recognition of this fact the Monday closest to May 1 (May Day) was made a public holiday in southern Ireland.

1990s

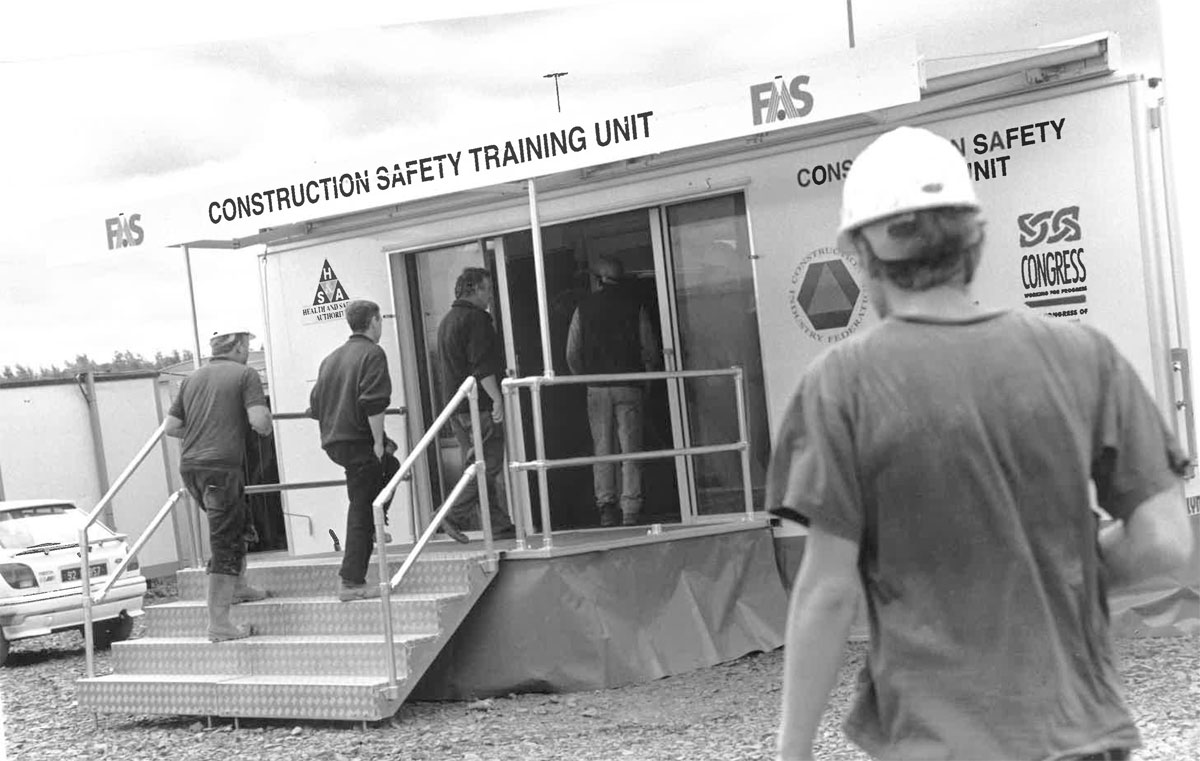

The era of centralised wage agreements which began in 1987 continued throughout the nineties and into the first decade of the twenty first century. It was characterised as the era of partnership.

This period witnessed a consolidation of unions through a process of amalgamation, a process which continues today.

A key issue for trade unions had been the struggle to secure union recognition as a legal right. This journey began with the industrial ,relations (amendment) act 2001,but this effort was negated by the supreme court in 2007 in a case taken by Ryanair.

2000s

Credit Tommy Clancy

The bursting of the property bubble in 2008 and the subsequent downward economic spiral placed the trade union movement in severe difficulty. In seeking to ascribe blame for reckless lending by financial institution and an over reliance of the construction sector, the commentariat decided that centralised wage bargaining was a key factor in causing the crash.

The partnership process collapsed in November 2009 when the government resiled from the national agreement. Since then Ireland has operated a mixture of local level and sectoral wage bargaining.

The sectoral bargaining process has been hindered by a succession of court challenges to the process where sectoral agreements can be given legal effect. This has meant a lost decade in the pursuit of workers rights. More recent judgements give hope that this era is coming to an end.

Note: A number of photographs have not been credited because the photographer cannot be identified at this time, despite efforts to do so. If you can identify any of the photographs , not credited, this will rectified.